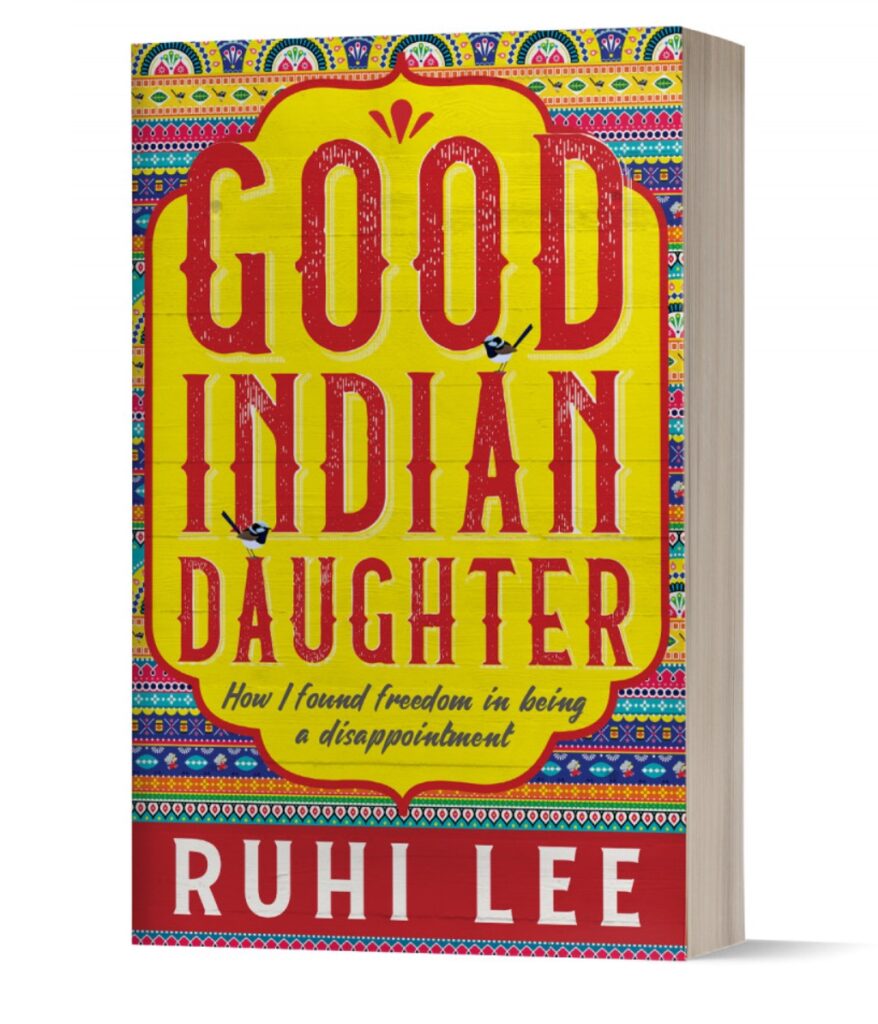

It is a great pleasure to have Ruhi Lee for our ‘Behind the Book’ segment. Ruhi writes on Boon Wurrung land. Her work has been featured in The Guardian, ABC Life, SBS Voices, South Asian Today, WILD magazine, and The Big Issue among other publications. Good Indian Daughter is her first memoir.

How did the love for reading begin?

Ruhi Lee- Back in primary school, I sometimes didn’t have anyone to play with during lunchtime or recess. When the bell rang, I often sought comfort in the library. I read so much that at the end of Years Three and Four, I won certificates for borrowing the most books in my year level.

I didn’t read much during my teenage years, but this changed in my late twenties, when I got pregnant. I quit my job and spent most of my time reading books on parenting. I was worried about the kind of parent I would be, so I set out to educate myself as much as possible.

This became one of several drivers for writing my memoir; I wanted to present a different, more respectful way of parenting compared to the, at times, toxic parenting I’d grown up with and witnessed other South Asian children, girls especially, grow up with in my community (not that all South Asian households were dysfunctional or any worse than households of other cultures – I’d have written about toxic parenting in many white families if I’d grown up in one but I stuck to my personal experiences as a South Asian). For readers who I believed would relate to my experiences and who might have thought about breaking the cycle of abuse under the guise of ‘parenting’ or guardianship, I wanted to water those seeds in their minds and offer solidarity and encouragement as a fellow parent trying to do the same. It’s hard to go against the current but I was showing myself, through my relationship with my daughter, that it was possible.

As I devoured my books on parenting and fell in love with reading again, I also purchased some fiction, memoir, and a lot of humour. I later bought books on the craft of writing. Today my bookshelf is overflowing.

It’s tough to believe you started reading at a later stage in life because you’ve clearly nailed the art.

Ruhi Lee- Thank you! I wouldn’t say I’ve nailed it, but I know what you mean. I engage and think deeply when I read, and I really pay attention when someone else is talking. This comes from a childhood spent studying others in order to imitate them, then hopefully be accepted by them. As you know from my book, I was such a chameleon. I would adapt to whatever environment I was put in. The downside of that is that I lived to please others, to gain their approval, and my existence was not an authentic one. However, the upside is that I became a quick learner, so, if you put something in front of me that I’m interested in, I’ll study it and absorb the obvious aspects of it quite rapidly. That’s probably how I picked up on some writing skills fairly quickly. Having said that, I’m worlds away from emulating the virtuosity of the writers I most admire.

Do you want to talk about the initial challenges that you may have faced while growing up?

Ruhi Lee- When I was in school, being Indian was not a desirable quality; it was funny to be Indian. My culture and heritage were something for other kids to laugh about or quietly cringe at. As I mentioned in the book, I had Mauritian friends, and they had brown skin too, but somehow, they were considered exotic while Indians were just viewed as unsophisticated unless they were Anglo-Indian. Some of my Mauritian friends could speak French and this was applauded, while nobody cared about the fact that I could speak Kannada or broken Hindi. I’m not saying that I should have been exoticised too. I just wish all of us children were accepted and treated equally for who we were.

But this is only one example of the challenges that come with growing up as a third culture kid, not to mention the psychological, physical, and sexual abuse the came from within and outside of my family. More on that in the book

I started working very early. I applied for my first job as soon as I legally could, at the age of fourteen and nine months. I worked in a supermarket for three years, then took a job as a concierge/receptionist for the management group of a shopping centre. I worked in childcare. I worked at a jewellers. I worked in event management. I’ve done a bit of everything. When I finished university, I got into a graduate program in HR and recruitment. While all of the above gave me an increasing sense of financial independence (though I regularly encountered challenges around racism, sexism and bullying), none of these jobs warmed my heart or caused my eyes to light up when I spoke about my work.

The turning point came when I discovered – contrary to what I was raised to believe – it was possible to pursue a ‘creative career’. No matter what I was told about needing to become a doctor or an accountant or IT professional, I eventually learned that the door to a creative career was one that South Asian women were allowed to walk through, that I was allowed to walk through. So I did.

And I plan to stay here for as long as I am able to work hard, find ways to cope with rejection, access the support I need and approach my chosen crafts with love and imagination. “The skin of an elephant and the heart of a poet” is what a storytelling career calls for, as Mira Nair so beautifully puts it.

It must have been hard to be brutally honest in a memoir. What kept you going with your writing?

Ruhi Lee- When I first started writing, I found out that globally, for every ten women who suicided, almost four of them were Indian women. And at the time, India had the highest youth suicide rate in the world. These statistics, shocking though not surprising at the same time, broke my heart. As someone who has been through depression and as someone who has been suicidal, I wanted to do something about it. I thought, what do I have in my hands? What sort of skills did I have that could help amplify the conversation around the oppression of so many South Asian women, even those in the diaspora?

I realised I could tell stories. I could tell my story. I’d grown to love writing and in particular, comedy writing. I was already writing about my experiences as an exercise in therapy, so I thought, why not share this? I kept going with it, and eventually it took shape as a book.

I knew I wasn’t starting a new conversation. Other people have already started it, but I believed that if I could add my voice to that conversation, I might help some women like me feel more seen or less alone in their experiences, or encourage someone to seek out therapy, or even just to be more open to telling her own stories, thereby emboldening someone else!

How has reading and writing shaped you as a person?

Ruhi Lee- I wasn’t a very articulate person growing up, in Kannada or in English. I spoke fluent Kannada until I was five years old. English is my second language and I only learned to speak it when I went to school. Eventually, the norm at home involved my parents speaking to me in Kannada, while I responded in English. My vocabulary was still underdeveloped even into my twenties. I would describe things in the simplest of terms, like ‘good’ or ‘bad’, ‘happy’ or ‘sad’. This meant that I had a black and white view of the world. My descriptions of concepts and emotions lacked nuance and accuracy. One of the worst aspects of this struggle became obvious when I was sexually abused at the age of eleven – I couldn’t even explain what had happened to my body.

Reading is such a gift. Through stories and poetry, other writers have gifted me with ways of being able to describe feelings, thoughts, and experiences that I’d never been capable of expressing through words. I also remember feeling shaken awake by Javed Akhtar’s TED talk on The Gift of Words and since then have taken my words, both spoken and written, much more seriously.

I now have a system for increasing my vocabulary in English – as I read, I highlight words I don’t know (I still find a lot). I underline these words, and when I am done reading the book, I go back, and I look up the definition of all those words that I didn’t know, write them on post-it notes, stick them up on my wall and I don’t take them down until I’ve absorbed their meanings and uses.

When I have the time and money, I plan to properly re-learn Kannada and Hindi so I can read and maybe even write in those languages one day.

What has been your biggest takeaway from writing your memoir?

Ruhi Lee- That I am capable. When I was at Uni, I could barely finish essays of 1500-2000 words and almost got kicked out of the institution for poor performance, for goodness’ sake. Now I’ve written a book of close to 90,000 words. I’ve proven to myself that with the right support, I can do anything I am interested in and/or passionate about.

I have made some people uncomfortable along the way, and will probably continue to, because I refuse to live in the boxes, they’d rather put me in. But what counts is that I have now demonstrated to myself that I am capable of seeing a major creative project through to the finish line and enjoying myself in the process.

I’ve also taken away that I can be assertive, that my honesty is powerful and saying ‘no’ is powerful. As a child, I rarely stood up for myself, rarely spoke my mind and rarely questioned people in authority. Developing competence and confidence in a language can help to increase confidence in oneself. I now know that I now have most of the tools to say exactly what I intend to say and back myself up without botching it up too much or freezing like I used to, because I didn’t know how to respond to confrontation.

How many edits did you have to go through for Good Indian Daughter?

Ruhi Lee- In 2019, I participated in a fantastic program called HARD COPY run by the ACT writers’ centre. I was required to take in the first thirty pages of my manuscript, attend masterclasses on the craft of creative non-fiction and rework those thirty pages. When I was selected for the final round of the program, on the basis of my improved excerpt, I had the opportunity to receive industry-level feedback from publishers and literary agents. Several encouraged me to have more confidence in my writing voice. I took that on board and wrote the rest of the book with that in mind, about eight drafts. Once it was acquired by a publisher, we did a structural edit, a copy edit and a proofread. So, ten to eleven edits in total.

How does it feel to see the labour of your love hitting the bookstores?

Ruhi Lee- It was strange at first. It came out on Tuesday 25th, May 2021 and Melbourne went into a lockdown that Friday. I couldn’t see it in bookstores until two weeks later when I did bookstore visits and signings in and around the city. I am full of gratitude now as I hear from readers. The fact that readers are coming back to me and telling me that they are feeling the emotions that I set out to evoke with this book is beyond rewarding.

Do you google yourself now that you’re a published author?

Ruhi Lee- I was googling myself before the book came out because I was curious to see what would come up, but I don’t anymore because I already know what’s out there, which bookstores are stocking the book and where it’s being promoted because the information is in my publicity schedule.

If you could, would you change anything in your journey?

Ruhi Lee- I’d have to think about how much of it is in my control. I would love to be closer to my parents and for us to have a more authentic, loving, and meaningful relationship, but I feel like I’ve done everything in my control to try to achieve that, and we haven’t really been able to get there. This has been a grieving process. At the same time, my bittersweet childhood has made me who I am, and I might not have found my vocation if it was smoother. Maybe I would? Who knows? But in general, I can’t think of any major personal decisions that I regret.

When you’re not writing, reading, or spending time with your darling daughter, what do we see you doing?

Ruhi Lee- I sometimes do a bit of macramé. On rare occasions, I make the time to paint. Oh, and I love my piano. I sit at my piano making music, and it just takes me to a completely different place. I enjoy spending time in nature too. Movies and TV shows in any language, especially comedies, are the best! Cooking and eating delicious food with loved ones, smooth jazz playing in the background, is one particularly divine way of living life to the fullest, in my opinion.

If the book got adapted into a Netflix movie, who do you think will make for a great main character Ruhi Lee?

Ruhi Lee- When did you last see a plus-size South Asian woman cast as a protagonist? If there was ever a visual representation of this memoir, it would be really important for me to see a plus-size South Asian woman play me in my twenties as I have fluctuated between size 14 and size 16 clothes for most of my adult life. But I’ve never seen someone with my shape and skin colour on screen without being the ‘funny best friend’ or the butt of jokes. So, if the book ever did get adapted, I would want those physical aspects of my existence to be honoured and for her to be taken as seriously on screen, as I am taken seriously in real life.

Is there any unfulfilled dream for you?

Ruhi Lee- Career-wise, I am moving toward a few goals. I’m currently working my way into screenwriting, but my long-term goal is to be a filmmaker while continuing to explore other forms of storytelling. I used to make movies as a kid. My sister and cousins were my cast. With them, I directed, filmed, and edited several school holiday thrillers! I’m still sad about putting down the camera and not picking it up for so many years other than to document life because I was made to believe that I had no business pursuing a ‘creative career’. I’ve been working my way back to the things that interested me as a kid before other people started telling me who I had to be. I hope I’ll get to write and publish some more books down the track. I have already started writing a novel and I’m currently working on a screenplay as well.

I do have some non-career-related dreams that are yet to be realised, but if I died today, I would die a very content person. I’ve lived and loved wholeheartedly. I’ve tried to do right by my kid, this planet, my loved ones; to give away excess material shit that means nothing and treat people with kindness. I’ve cried at the Hamer Hall listening to the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. I’ve eaten Pani Puri, Pav Bhaji and Pista Kulfi to my heart’s content. I’ve signed my will. My funeral has been planned (refer to chapter 13 of my book). But if any of the dreams in the above paragraph came to fruition, I’ll be as thrilled as I was when I achieved past goals.

Good Indian Daughter, is out now, through Affirm Press. You can find Ruhi online at ruhilee.com.